I

On Seeing a Benin Mask in a British Museum (1977)

BY NIYI OSUNDARE

Here stilted on plastic

A god deshrined

Uprooted from your past

Distanced from your present

Profaned sojourner in a strange land

Rescued from a smouldering shrine

By a victorianizing expedition

Traded in for an O.B.E.

Across the shores

Here you stand, chilly,

Away from your clothes

Gazed at by curious tourists savouring

Parallel lines on your forehead

Parabola on your cheek

Semicircles of your eye brows

And the solid geometry of your lips

Here you stand

Dissected by alien eyes.

Only what becomes is becoming

A noose does not become a chicken’s neck

Who ever saw a deity dancing

langbalangba

To the carious laugh of philistine revelers?

Ìyà jàjèjì l’Ẹgbè

Ilé eni l’ẹ́só ye’ni

Retain the tight dignity of those lips

Unspoken grief becomes a god

When all around are alien ears

Unable to crack the kernel of the riddle.

II

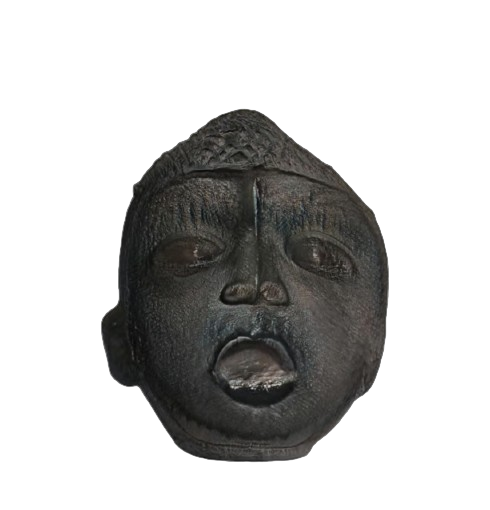

DESHRINED ANCESTORS (2024)

BY MINNE ATAIRU

"Enough ivory may be found in the King's house" to finance the invasion of Benin Kingdom

[ I ].

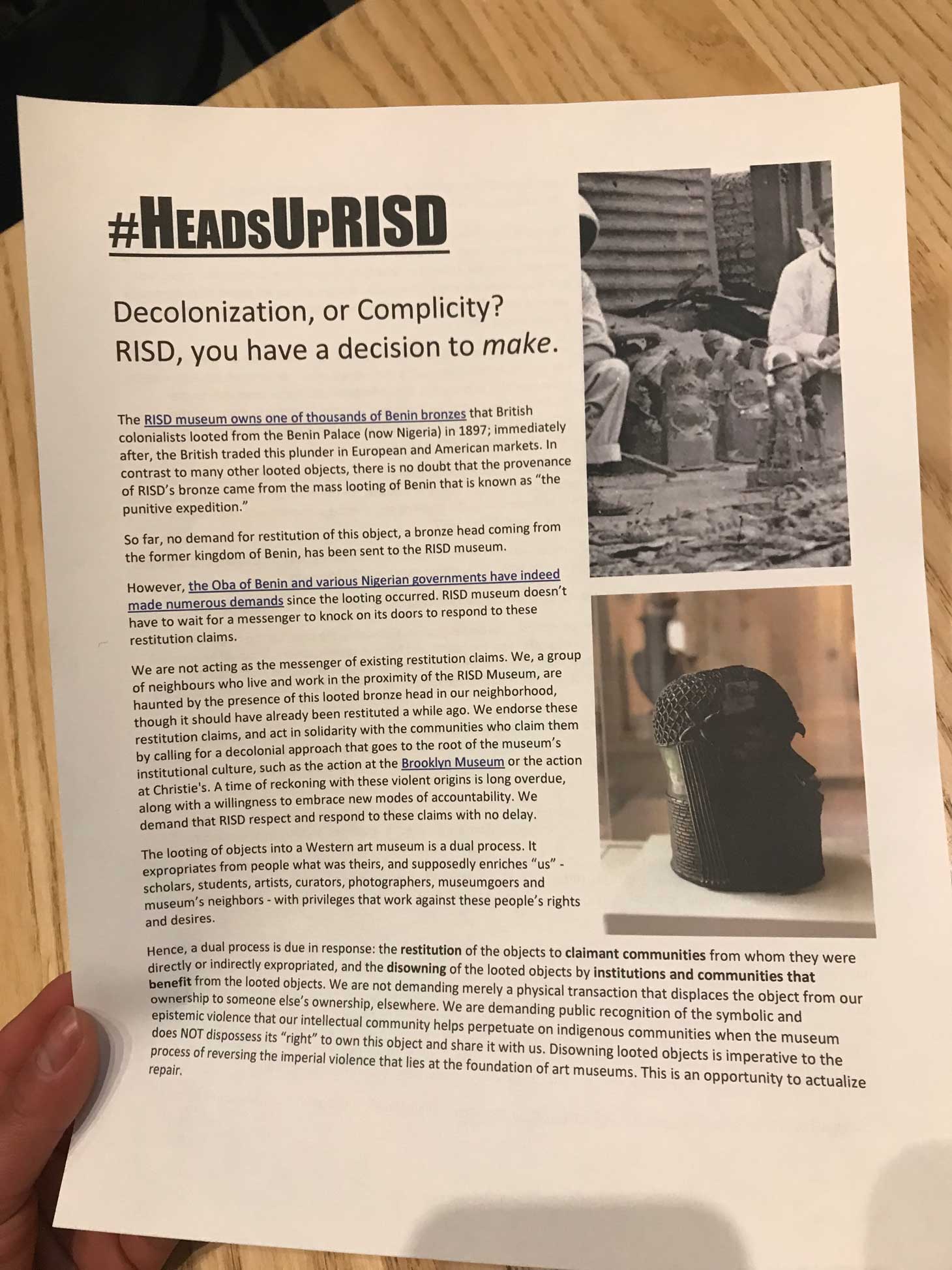

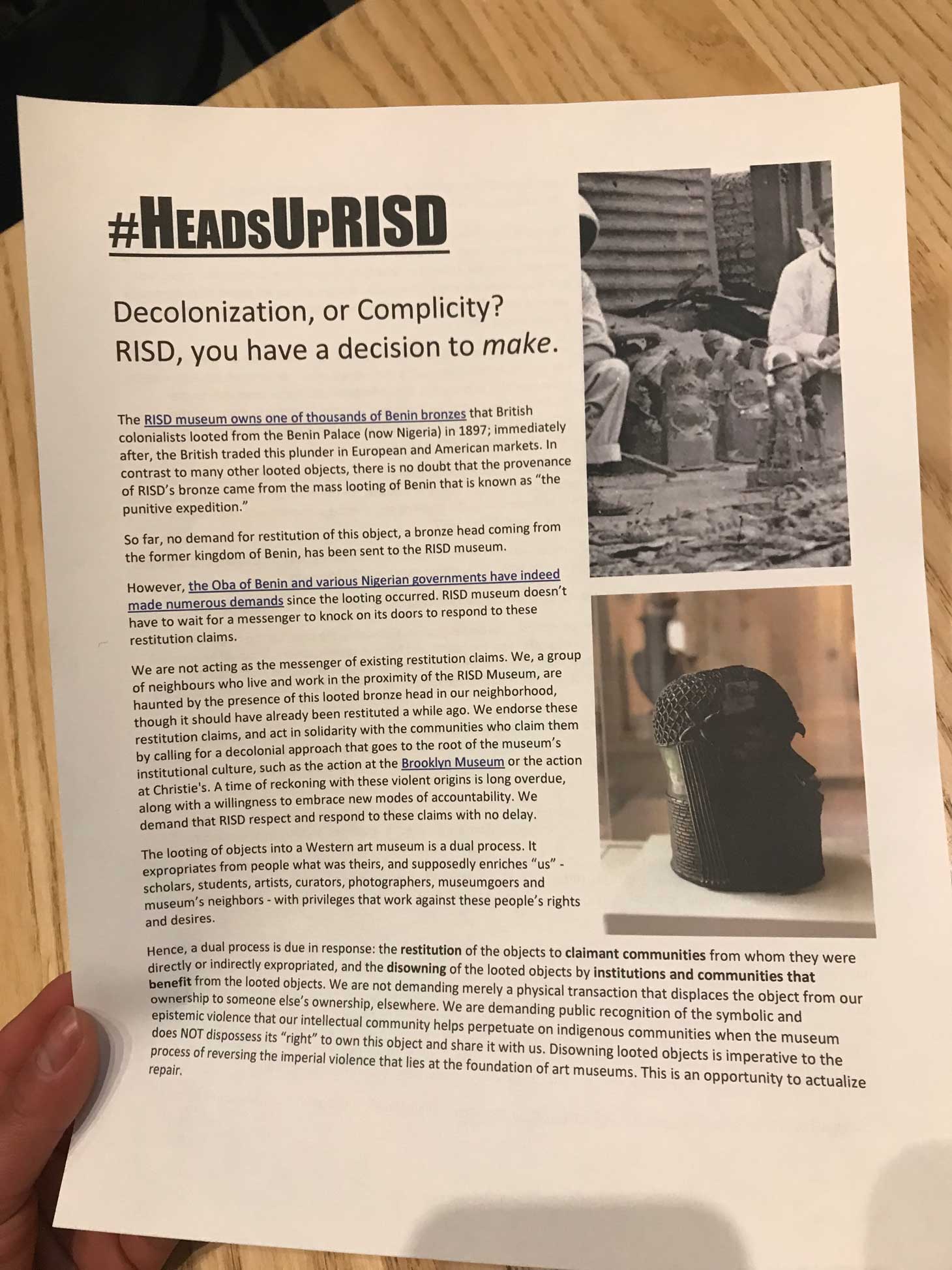

The 1897 British invasion

of Benin was fueled by colonial intelligence reports

[ II ] that identified the

Kingdom's natural

and material

wealth

including sacred and secular objects made of bronze, wood, terracotta, ivory,

iron, coral, and leather. Armed with this knowledge, British soldiers razed the royal palace—a cultural

epicenter

that housed artist studios, residencies, and repositories of imported art materials. Amid the chaos, Oba

Ovonramwen-the Kingdom’s sole patron of the arts, was deposed and

exiled. The royal archive, rich with centuries-old artifacts, was looted and divided into

"official" and "unofficial" spoils. These looted artifacts, later termed "Benin Bronzes", were shipped

to England.

There, the "official booty of the expedition" was auctioned to "defray the cost of pensions" for the

colonial forces

[ III ]. A curator's 1898 ledger titled "Fate of the Benin

Bronzes" documents

their

distribution to

prominent institutions including the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum, Horniman

Museum

[ IV ].

Over a century later, these looted artifacts remain in the collections of 160

[ IV

] Western museums.

The 1897 colonial upheaval led to an exodus of artists from Benin city to satellite towns. In their new

homes, Benin artists were compelled to abandon their craft and take up subsistence farming. This period of

displacement marked the beginning of a 17-year artistic recession (1897-1914) for which no visual or

archival records have survived.

To address this dearth in archival documentation, I began a speculative project titled Igùn AI

[ V ]. The project

is

guided by two questions:

- What artifacts might have been

produced during the 17-year artistic recession?

- What alternative materials and artistic processes might displaced artists

have adopted?

In Igùn: Prototypes I—IX, I utilized StyleGAN2

[ VI ] , a machine learning

algorithm to

generate speculative images and videos. The process involved fine-tuning the algorithm

on a dataset of images depicting looted Benin Bronzes. While the speculative

outputs

provided invaluable insights into the aforementioned questions, the process also revealed two critical

limitations.

First, dimensionality: StyleGAN2 is designed for two-dimensional image synthesis. The model learns and

generates patterns solely on two-dimensional data, and therefore, lacks the capacity to

extrapolate those

patterns into three-dimensional forms. This constraint posed a challenge in rendering the spatial and

volumetric qualities that are integral to Benin’s sculptural tradition.

Second, materiality: StyleGAN2's learning process is heavily influenced by the characteristics of a dataset.

In

this case, I fine-tuned the model on a

dataset that primarily featured images representing bronze and terracotta objects. Consequently, the model

exhibited a bias towards these materials, which in turn, narrowed the scope of my material exploration.

The above outlined constraints have prompted the next phase of my research: a transition from

two-dimensional

to

three-dimensional generative models.

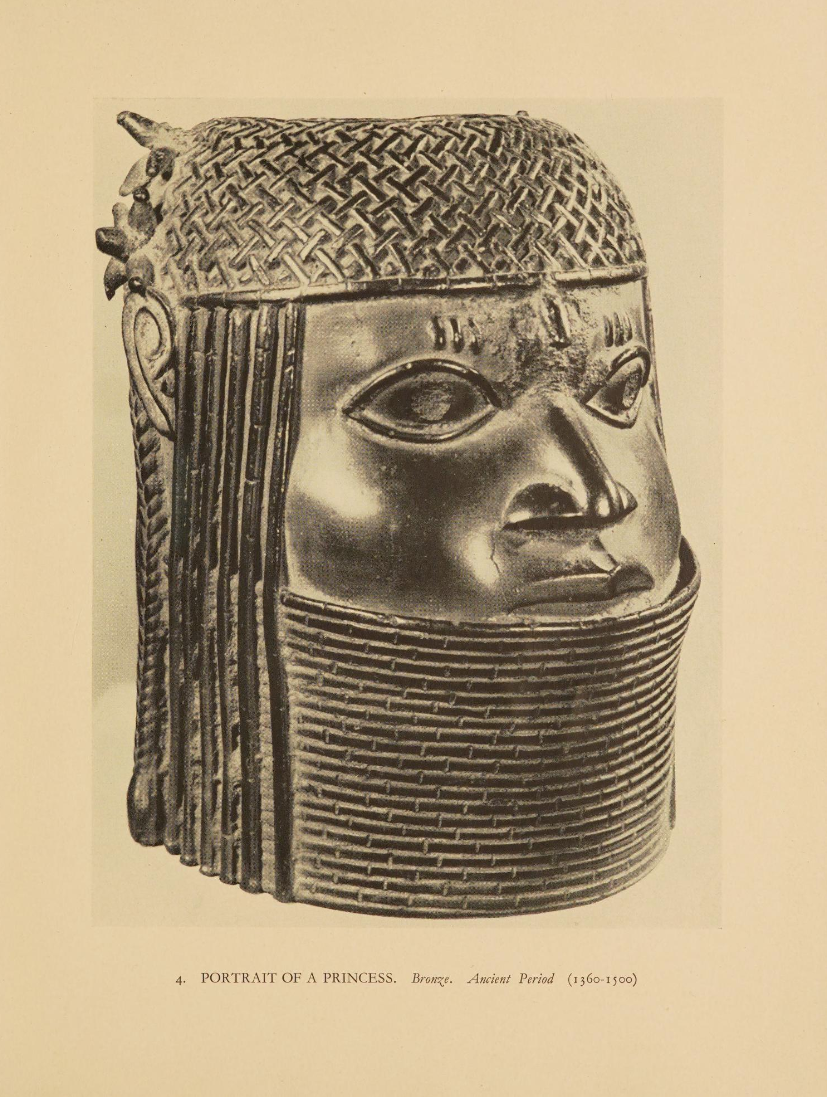

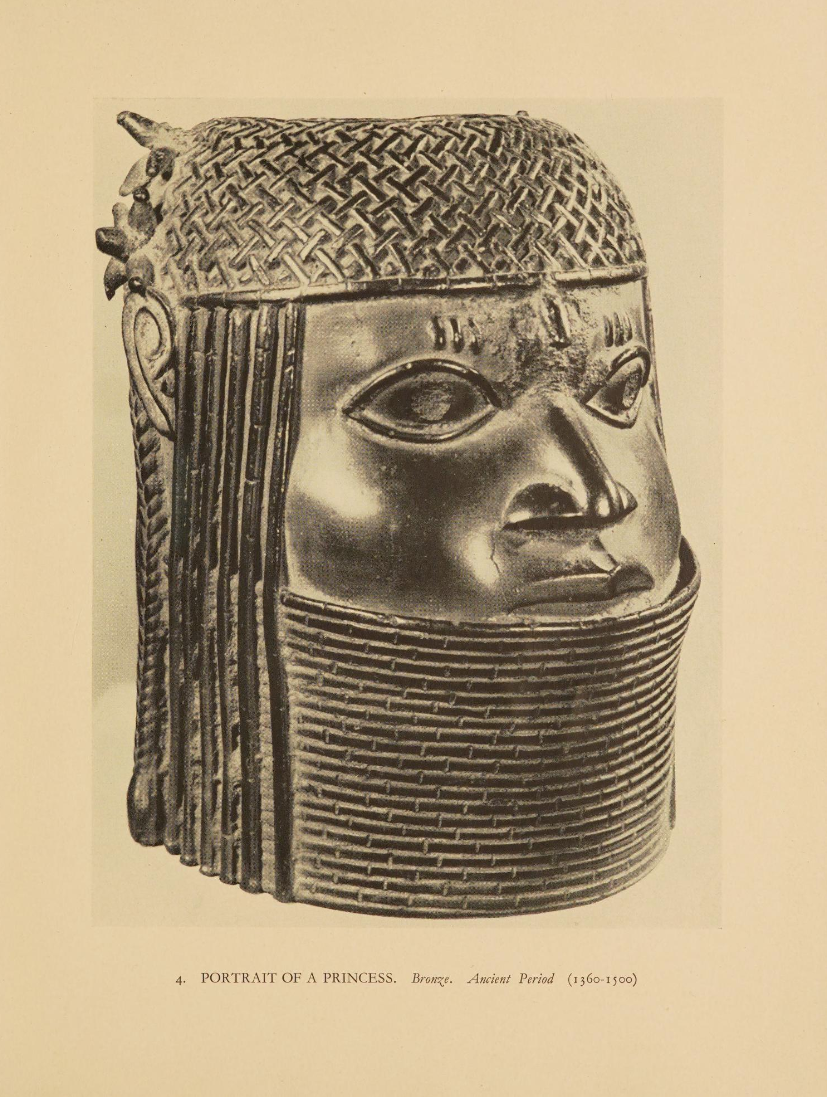

For centuries, Benin artists have

demonstrated mastery over three-dimensional forms—from classical sculptures depicting commemorative

portraits of

royalty and divinities to contemporary reproductions crafted for a tourist-driven market. This rich artistic

legacy demands a conceptual approach that fully honors and embodies the depth of three-dimensionality.

Advancements in text and image-conditioned 3D generative models have been instrumental in

overcoming the limitations of StyleGAN2. Models such as Rodin Diffusion

[ VII ]

enable the synthesis of

volumetrically and

geometrically

consistent three-dimensional graphics that better align with the material and spatial qualities of Benin’s

sculptural

tradition. My current research is driven by two questions:

- To what extent can I synthesize 3D structures that mirror the visual characteristics of the images

and videos generated for Igùn: Prototypes I—IX?

- To what extent can the synthesized 3D structures faithfully reconstruct the occluded

regions of the images and videos generated for Igùn: Prototypes I—IX?

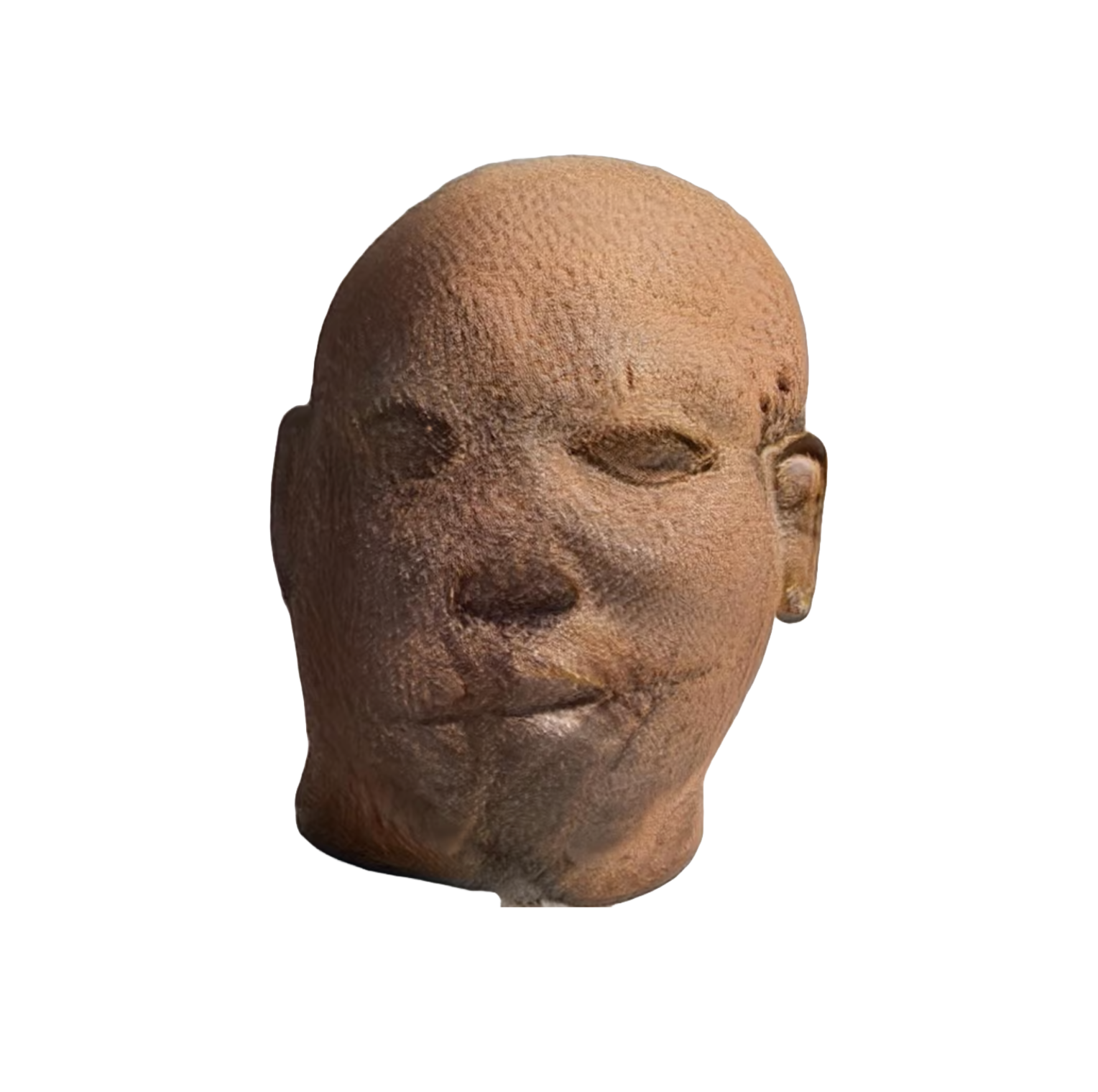

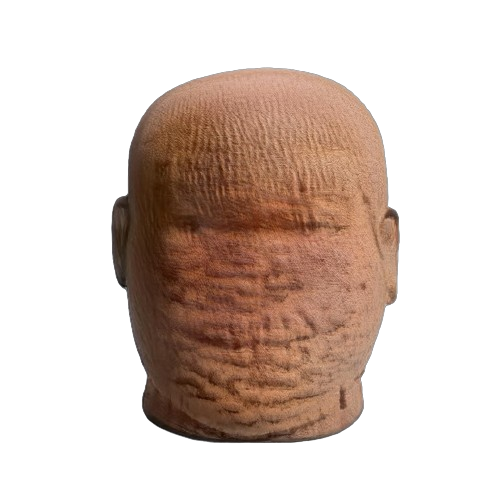

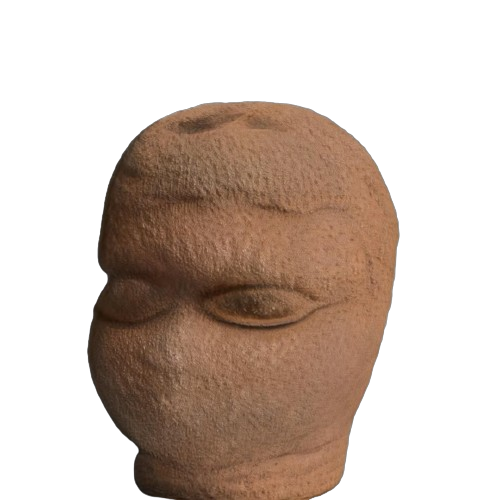

My research questions are investigated and visualized through an augmented reality (AR) sculpture titled

"Deshrined

Ancestors" (2024). The digital sculpture is an assemblage of sixteen AI-generated artifacts

curated from

ten generations of foundational and fine-tuned machine learning models (2020-2024) developed for Igùn:

Prototypes I—X. The models utilized to address the challenge of dimensionality include:

I

Image Synthesis 2020-2022

StyleGAN2 models fine-tuned on a dataset of looted Benin Bronzes.

II

Text-to-Image 2021-2022

Text-guided image generation models fine-tuned on variations of the looted

Benin Bronze dataset.

III

Text-to-3D 2023

Three-dimensional models generated from text prompts.

IV

Image-to-3D 2024

Three-dimensional forms synthesized from two-dimensional images generated

with earlier models.

III

The Rubber Regulations of Benin (1898-1899)

To address the challenge of materiality, I imported my resulting AI-generated 3D-dimensional objects into

a 3D rendering engine that utilizes Physically Based Rendering (PBR)—a technique designed to simulate

various material properties under real-world conditions. Leveraging this approach, I

chose to simulate rubber—a malleable material that could plausibly have served as an alternative artistic

resource for displaced Benin artists.

Importantly, this material selection holds artistic significance when examined through the lens of

colonial-era

resource extraction

and exploitation in Benin.

The 1897 invasion of Benin drew attention to the region’s rubber

[ VIII ]

forests-a high-demand resource for the

production of industrial goods, such as hoses, tubes,

springs, washers, diaphragms. To maximize rubber extraction, colonial authorities implemented regulations

that

aggressively promoted rubber exploitation "to the utmost." These policies systematically dismantled Benin's

centuries-old land-use practices, including an eight-year fallow period,

permissionless farming on virgin land, and prohibition against farming in "evil/sacred forests" (Indigenous researchers have since explained that prohibitions against farming "evil/sacred forests" played a crucial role in forest conservation.

[

IX ]). To ensure compliance, colonial authorities offered £2 rewards to

informants who reported those still upholding precolonial land-use practices.

By 1899, colonial authorities had established 250 nurseries to cultivate rubber seedlings for the

development

of

"communal

plantations." These plantations expanded rapidly: from 126 in 1903, they expanded to 1,050 by 1906, 1,629 by

1907, and reached

2,251

by 1908

[ IX ].

European companies were also incentivized to exploit Benin’s rubber resources. For example, in

1905, Miller Brothers

acquired 500

acres for a rubber plantation and expanded by another 560 acres in 1911. By 1908, J.G.M Cranstoun and

Company owned two plantations covering 1,280 acres. By 1927, Messrs. MacIver Holdings controlled 2,021 acres

of rubber-producing land. Other companies involved in rubber exploitation included the Nigerian

Mahogany and Trading Company, MacIver and Palmer, United Africa Company, Bey and Zimmer, The African

Association, and The British Cotton Growing Association

[ X ].

Colonial records further underscore the magnitude of rubber extraction during this period. The "Annual

Report of the Colonies, Southern Nigeria" documented rubber exports of 2,251,315 lbs in 1900, 1,740,156 lbs

in 1901, 865,834 lbs in 1902, 1,656,000 lbs in 1907, and 713,000 lbs in 1908. These fluctuating figures

reflect the consequences of overexploitation and the subsequent decline in rubber yields

[ XI ].

The enforcement of these rubber regulations not only accelerated colonial extraction but also

criminalized

[ XII ] the indigenous population.

For

instance, in Regina v.

Osufu Jebu,

Sumola, and Bakari, the defendants were charged with smuggling "adulterated and very offensive" rubber. In

Regina v. Ground Nut, Jack, and Josiah, the accused were apprehended with "a lot of tools, etc., used for

working rubber." In Regina v. Thomas Ouami, the defendant was accused of leading a gang of illicit rubber

workers. Similarly, in Regina v. Ipapa, Ehenua, Obasuye, Asaota, and Jegede, the defendants were identified

as

members of a group of 150 illicit rubber tappers. Additional cases, such as Regina v. Gbeson and Aburonke,

Regina v. Adeanju, Regina v. Lawojo and Omoleye, Regina v. Akinbo, Regina v. Aluko, and Regina v. Jagbohun,

involved charges of "illicit rubber working" or "working rubber without a license."

While colonial-era rubber prosecutions are well-documented, much less is known about the lives of those

prosecuted. Among them could have been the very artists who once thrived under the Oba's

patronage. This uncertainty invites further speculation: Could some of these defendants have been displaced

artists? Artists who might have turned to full-time farming out of necessity? And if so, might they have

found ways to repurpose their "illicit" rubber tappings for artistic production?

VI

TECHNICAL NOTES

Deshrined Ancestors (2024) is a digital assemblage of sixteen AI-generated 3D artifacts curated from ten

generations of

foundational and fine-tuned machine learning models (2020-2024), developed for Igùn: Prototypes I—X. Each

artifact is labeled with a title (e.g., Prototype V), corresponding to its sequence across these ten

generations.

The piece is interactive in browsers and viewable in

Augmented Reality (AR) via mobile. The AR feature, exclusively available during exhibitions, overlays the 3D

sculpture onto a platform that

once housed a classical Benin Bronze at the RISD Museum from 1939-2020.

AR engine: model-viewer by Google.

Web Rendering: Three.js Mentor—a GPT developed by ThreeJS.

VI

REFERENCES

- Eyo, E. (1997). The dialects of definitions:" Massacre" and" sack" in the history of the Punitive

Expedition. African arts, 30(3), 34.

- Coombes, A. E. (1996). Ethnography, popular culture and institutional power: narratives of Benin

culture in the British Museum, 1897-1992.

- Read, C. H., & Dalton, O. M. (1898). Works of art from Benin City. The Journal of the Anthropological

Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 27, 362-382.

- Eyo, E. (1997). The dialects of definitions:" Massacre" and" sack" in the history of the Punitive

Expedition. African arts, 30(3), 34.

-

See: institutional estimate according to a 2021 Global survey of Benin Bronzes via The Art Newspaper

- Atairu, M. (2024). Reimagining Benin Bronzes using generative adversarial networks. AI & SOCIETY,

39(1), 91-102.

- Viazovetskyi, Y., Ivashkin, V., & Kashin, E. (2020). Stylegan2 distillation for feed-forward image

manipulation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020,

Proceedings, Part XXII 16 (pp. 170-186). Springer International Publishing.

- Wang, T., Zhang, B., Zhang, T., Gu, S., Bao, J., Baltrusaitis, T., ... & Guo, B. (2023). Rodin: A

generative model for sculpting 3d digital avatars using diffusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF

conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4563-4573).

- Ikponmwosa, F. (2020). Colonialism and Industrial Development in Benin Province, Nigeria.

Romanian Journal of Historical Studies, 3(1), 20-29.

- Egboh, E. O. (1985). Forestry policy in Nigeria, 1897-1960. University of Nigeria Press.

- Fenske, J. (2013). “Rubber will not keep in this country”: failed development in Benin,

1897–1921. Explorations in Economic History, 50(2), 316-333.

- Southern Nigeria Annual Report for 1900.